|

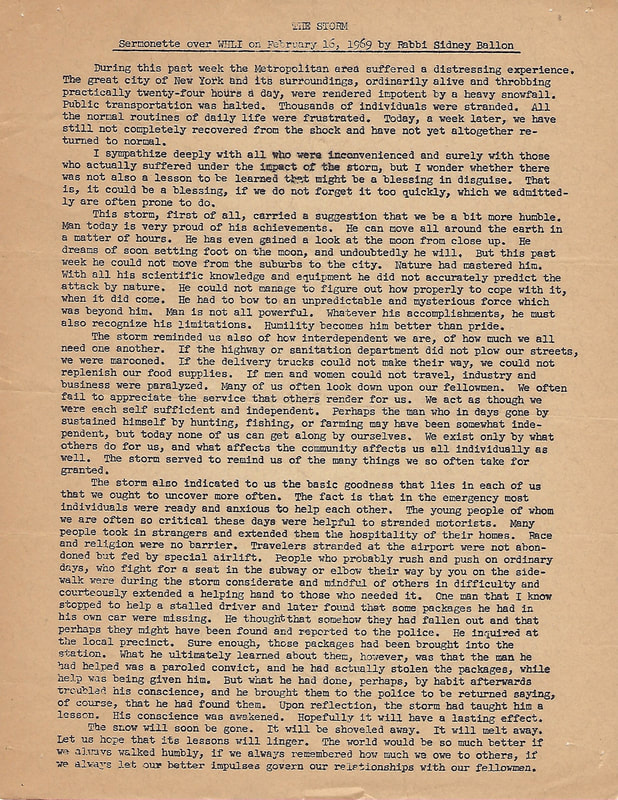

My father's radio sermonette from 1969 speaks to today's coronavirus crisis. [We] had to bow to an unpredictable and mysterious force which was beyond [us].

Yesterday there was a stranger in the side yard of our home, not particularly well-dressed, asking to come into the house. I didn’t know who he was. I didn’t know why he was in our yard. I didn’t think he belonged there. I was reluctant to let him in. When I refused him entry, he made menacing gestures and remarks. Then, fortunately, I woke up.

This morning my dream was less threatening and was easily understood. There was no metaphor about the threats we may feel to our secure environments. It was a literal conversation, if not harangue, about the dangers of the pandemic. I was being admonished for touching my face. I woke up with an urgent feeling that I needed to wash my hands. It doesn’t take a Joseph to realize that coronavirus has invaded my dreams. For this I’m actually grateful. I don’t believe there are any bad dreams. Each dream carries an important message. When my subconscious causes me to pay attention to things I’ve been overlooking, it’s up to my conscious mind to do just that—to inquire of the dream, what is it that I am missing here? Sometimes I do that quite literally. This morning I didn’t go through a formal dream interpretation process, but I did notice the thoughts that arose in the few moments after I awoke. Like many of us, I noticed that in recent days there are people who are reaching out, demonstrating kindness and concern, and that I too have had a greater urge to reach out to others. Names from the past keep floating through my mind. Why would I think about a boss that I had nineteen years ago—other than to realize how important his wisdom and his kindness was toward the success of my career. Why would I think about a classmate from nearly fifty years ago—except to realize the importance of a friendship that has endured over the decades. In the current climate I feel the urge to do more than think about the people who have made a difference in my life. I have begun contacting them. A question that continually goes through my mind takes me back to the two and a half years during which my brother was living with the severe diagnosis and prognosis regarding his glioblastoma—his terminal brain cancer. It was a time in which I watched him go on a pilgrimage of love. His heart was wide open. He went everywhere he could, searching for old friends and family to give love and blessings. In his fragile condition, he traveled from his home in Alabama to South America, twice to Europe, multiple trips to New York and California, and I’m sure lots of places I’m not even aware of. Everywhere he went he was bestowing love and blessings. I’ve always wondered why it takes a fatal diagnosis for someone to be able to open his heart in such away without being considered crazy. I still don’t have the answer, but I am aware of the opportunity that this pandemic offers. Suddenly all of us are facing an existential threat. Never before have so many people been aware of the reality that has tacitly accompanied them every day of their lives—that they and their loved ones are mortal. With that awareness comes greater permission to be loving without being thought insane. Before coronavirus, consciousness of one’s own mortality was not all that accessible to most of us. Intellectually, we all knew that we would die, but it was much harder to deeply take in that awareness and get a full sense of the finitude of our lives, not to mention the harsh reality that even the next day is not guaranteed. Every day we would walk through life with a sense that I’ve got this. Things are under control. I can make plans with clear expectations that they will come to fruition. That’s no longer the case. The sense that things are under control was always an illusion. Nothing is that certain. Now many of us are experiencing the discomfort of uncertainty and the fear that accompanies it. Uncertainty is actually pretty powerful. It strips away the illusion that things are under control. With that comes gratitude for each day we are given and for the opportunity to continue to learn, to create, to be in relationship, and to make a difference in the lives of other people. The Psalmist said, Teach us to number our days that we may nurture a heart of wisdom. He didn’t say a brain of wisdom. We already know everything we need to know about our mortality. With a heart of wisdom we may understand how precious each day is and how precious each life is. If we use these days of global crisis to nurture a heart of wisdom, we will grow in our capacity to be open, to reach out, and to bestow blessings and love. In 2008 I was among over a hundred cyclists who rode from Jerusalem to Ashqelon down through the Negev to Eilat, approximately three hundred miles. Upon my return I spoke to the congregation about the impact the ride had on me. The words I spoke then, that continue to linger in my mind, are as follows-- There were quiet moments too, when the group had spread out, when I had the entire road to myself as far as I could see. As alone as I was, with little to be heard other than the sound of my own bicycle rolling across the pavement, I would still feel secure in knowing that I was part of an amazing supportive, loving community. To be that alone and feel that connected was very sweet. What brings this to mind today, is yesterday’s experience of worshipping virtually with the streaming Power Hour minyan. In some ways this was the most “powerful” Power Hour of all. I felt emotional twinges throughout, as I imagined my fellow congregants, absent from the empty pews that the video camera unintentionally and ironically focused upon. I was filled with appreciation at the challenge Michael, Bill, and Rabbi Ezray not only accepted, but generously and bravely met in deeply connecting with us despite the discomfort of speaking to an empty room.

I sit next to Debbie almost every week in the Beit T’fillah. This week we were together, but sequestered to my home office, viewing the service on my computer screen. I donned my kippah and tallit this Shabbat, as I would normally do in shul, but not normally do at my desk. It was an important part of creating the ritual space, as we brought our full imagination to conjure up the people and the place from which we were separated. In addition to feeling connected to the virtual community, there was another unanticipated benefit as I more keenly appreciated the blessing of having Debbie at my side. The service was reminiscent of the virtual funeral I facilitated by conference call when my mom was buried shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. That day, since travel was so uncertain, twenty friends and family dialed in from around the world. From their reports, some callers’ experience of the funeral was more vivid and emotionally charged than for those at graveside. I likened it to listening to old-time radio where listeners had to bring their imaginations to the broadcast, rather than passively receive images as on television. None of us knows how long we will have to sustain this virus-imposed segregation. The more we experience “social distancing” the more we realize how dependent we are on social connection. Thank God, and thank Congregation Beth Jacob that we can still feel secure in knowing that we are part of an amazing supportive, loving community. To be this alone and feel this connected is very sweet. V’shamru v’nai-Yisrael et-hashabbat… The Children of Israel shall keep the Sabbath… Exodus 31:16 Keeping the Sabbath—what does it mean? As a kid, growing up in the home of a Reform rabbi in Metropolitan New York, in the Fifties and Sixties, I had a pretty clear understanding of what it meant to observe Shabbat. (I didn’t equate that with keeping it or guarding it as the term Shomer Shabbes translates.) There were just certain things we were expected to do or not do in order to observe Shabbat.

In our home, throughout the week we ate dinner as a family at six o’clock sharp—every day. Family dinner on Shabbat was a cut above. Tablecloth. Good china. Candles. Kiddush poured from my grandmother’s cut glass decanter. Challah. A special meal. When we got to a certain age we regularly joined the folks at services, as well. Saturday was more about what we did not do. We didn’t work. It was probably the one day of the week that one or more loads of laundry did not tumble in the machines in the basement. We did not engage in commerce. There were no shopping trips per se. There were some exceptions. The West Hempstead Rams played their football games on Saturday afternoons, and basketball on Friday nights. There were the occasional Friday night dances. If we had to dip into our pockets to pull out a quarter for entry to a high school event, that wasn’t exactly shopping. I suppose that Dad was less than thrilled that we were going to these events, but he must have decided to be selective about picking his battles. Our family was not Shomer Shabbes. We were Reform Jews. We drove to temple. We turned lights on and off. We tore toilet paper. Relative to some of my peers, however, we were pretty far to the right. We toed the mark my father set, one that hardly existed in other households. A generation later, as I pretty much set the standard for Jewish observance in the home we created in Palo Alto, family life was somewhat different. Our children had many extracurricular activities. Five of us gathering at the same table, at the same time, night after night, was a rarity. The one constant, however, was Shabbat dinner. On Shabbat, the kids were expected to be home for dinner—tablecloth, candles, good china, kiddush poured from my grandmother’s cut glass decanter, challah, and a special meal. About twenty years later, as I was attending Davvening Leadership Training Institute. I was talking with my instructor, Rabbi Marcia Praeger. I don’t recall the exact content of the conversation, until the moment when I said to Marcia, somewhat apologetically “I’m not Shomer Shabbes,” to which she replied, in so many words, “We all get to decide how we choose to guard Shabbat. We don’t have to let others define that for us.” What a validating and liberating declaration! That’s how I became Shomer Shabbes—not from becoming more stringent in my practice, but in honoring the practices I maintain to keep Shabbat alive in my life, for me and my family, and for Israel. My father spoke from the bimah more than once about how liberal Jews of the day should not define their Judaism by what they don’t do --I don’t wear a kippah, I don’t keep kosher, etc. They must bring their minds and their souls to the task of understanding what, among the mitzvot, rings true for them, what they choose to practice in order to add meaning to their lives. When I reflect on those formative years in my parents’ home, I recall how, as a member of the high school marching band, I had a regular Saturday afternoon gig throughout the fall, supporting the football team and entertaining the crowd with music. On one of those days, quite unexpectedly, and to my great delight, Dad miraculously appeared at a game. He must have, on that autumn day, weighed the value of family versus that of Shabbat halachah, and family rang true for him. The Union Prayer Book with which I grew up, contains a notable line from the Zionist thinker, Ahad Ha’am, “Even as Israel has kept the Sabbath, so the Sabbath has kept Israel.” In an era where new paradigms of Jewish practice are evolving, exactly how that’s done is up to each one of us.

This saga may have started on a fall day in 1928 when my dad, Sidney Ballon, first stepped on the Brown University campus as a freshman. Regardless, this has been a story long in the making. Dad and his younger brother, Herbie, the “Ballon boys” of Providence, were much heralded in their day. They took all the math and Latin awards at Classical High School, or so legend has it. They were both Phi Beta Kappa at Brown—Dad in the Class of 1932. The next generation benefited from their legacy. I don’t know about my brother, Jeff, five years my senior, but as for me, without legacy my high school grades alone surely would not have merited admittance to Brown. Yes, I had board scores showing a lot of promise, but face it, I neither knew how to study nor why one would bother. At the time, I was not ready for East Podunk Community College, let alone Brown. But I got in with the fervent hope that the small size of the school would provide a nurturing environment in which my potential would be realized. It didn’t. In addition to my having developed no discernible study skills, being practically devoid of intellectual curiosity, and possessing a prefrontal cortex very much “under development,” I also suspect that underlying that shaky intellectual foundation was even less stable psychological soil. I’ve come to believe that personal demons were at work, anxious to prove to me and to the world that I was unworthy. Simultaneously, they may have been striking back at my father for putting me in this untenable position. With all that at work, it’s a wonder it took me five semesters to flunk out! Chalk that up, I suppose, to perseverance. I had been skating on thin ice most of the way. During the fall semester of my junior year, I cleverly, if unconsciously, assured my academic demise and subsequent departure by scheduling a full slate of morning classes while virtually sleeping until noon every day. That allowed me to avoid the discomfort of sitting in a class for which I was unprepared. It also gave me a wide open afternoon and evening to pursue my real interests: intramural sports, marching band, writing scandalous halftime shows, playing bridge and hearts, and general horsing around with my buddies. (Okay, I did show up in the art studio by and large, but even there, my instructor questioned my commitment.) It’s only conjecture, fifty-one years later, but I have to assume I experienced as much relief as remorse when the hammer finally came down. And the guilt—yeah, there was a healthy dose of that. It was aided and abetted by Jeff, who had managed to squeak through with the Class of ‘64, and who may have taken a small measure of glee by bluntly declaring to me that I was “killing Dad.“ The fact is, by my dismissal, I got all that I had long, but unconsciously wished for—a ticket out. It was Jeff‘s fate (or choice) to follow in our father‘s footsteps—Brown, Hebrew Union College, ordination as a reform rabbi, service as a chaplain in the United States military, a pulpit in the south, a pulpit in the north. I, by contrast, could now cash in my golden ticket to do anything and everything else that life offered. What a relief! What a ride! The following autumn I miraculously found myself in a tiny art school in Portland, Oregon—yes, three thousand miles from Providence! It was the late sixties. Tune in, turn on, and drop out was the mantra. While I didn’t push that to its extremes, I, nonetheless, enjoyed a great burst of creativity and a refreshing breath of freedom. And yes, Jeffrey’s admonishment went with me wherever I went—mostly unconsciously, sometimes bursting through in judgment, shame, and anger toward myself and others. I have to accept my role in nurturing the shame throughout the years. Dad’s gone. Jeff’s gone. Of what use was it for me to perpetuate shame thrust on me for simply doing what I had to do? As the poet, Mary Oliver put it:

There should be no villains in this story—just understanding, acceptance, and forgiveness. We all did all we could do, all we knew how to do, under circumstances not entirely of our making. At last, I’ve concluded that half a century is sufficient purgatory. To put it in another context, what do today’s youngsters do when they aren’t quite ready for college? They exercise the option of taking a “gap year”—not a socially acceptable approach, or one even given consideration back in the sixties. Aha! How clever of me! Ahead of my time! I unwittingly created my own “gap year”—albeit two-and-a half years, albeit at great expense, albeit nonsensically on a college campus instead of a worthy alternative. And what did I accomplish in the “intersession“ of my own making? I met a lot of unmet needs that were critical to my development and to preparing me for a life of learning—just as a gap year should. Perhaps the greatest need that was met at Brown, in sharp contrast to my life at West Hempstead High School, was a sense of social ease. In high school I was known to one and all as “the rabbi’s son” and suffered from more than the typical adolescent alienation. Whereas, at Brown, no one knew or cared who my father was. I was one of the guys! I had buddies. We played cards and sports, watched the original Mission Impossible and Batman, had meals together in the refectory, hung out in the dorm. I fit in! One rewarding similarity with high school was how I took a leadership position in the band. At Brown, due to the nature of the largely student run organization I had an even greater role than in West Hempstead. It wasn’t long before I became part of the comedy writing team responsible for the aforementioned scandalous halftime shows. Later, when I became president of the band, I used my art skills to create a cartoon self-portrait as a “mascot” logo that, much to my surprise was, in later years, dubbed Elrod Snidley, and is still in use today—my legacy to Brown! (3) Meanwhile, my frontal cortex was slowly developing, such that academic pursuits subsequent to Brown were highly successful—an artistic achievement award from the University of Judaism, dean’s list and a bachelor’s degree in education from Hofstra, a Master of Architecture from Yale, to wit. Yes, Brown provided a virtual and formidable “gap year.“ I am proud of my achievements there and all that they led to throughout my academic and professional life. I didn’t come to this realization in a single flash of insight and clarity. It was a process. It took some time, some deep probing, some work. Strange as it may seem, I owe a lot to my dreams—not the aspirational kind, but the one’s that come in the middle of the night. I’ve long paid attention to them, and especially so in the last few years. I have a friend with whom I regularly meet to support each other in sifting for the subconscious messages to be found in our dreams. I have a spiritual director who has expertise in doing dream work in a spiritual context. And I have worked with a Jungian therapist for whom my dreams provide fertile ground for psychological exploration. I can’t say exactly when and where among these resources I finally put all the pieces together. That’s part of the magic of living an “examined life.” In his book, From Age-ing to Sage-ing, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi says that part of a constructive approach to aging is to make amends with the past by recontextualizing one’s life. Having finally reframed the joys and sorrows of my Brown experience, there was only one thing left for me to do. For the reader to appreciate this next point, I must describe a piece of Brown University lore. Brown’s Van Wickle Gates provide a ceremonial entrance to the campus. The monumental main gates are flanked by two smaller side gates that remain open throughout the year. The central gates, however, remain locked except for the first day of each semester when they open inward for incoming students and on Commencement Day each May, when they swing outward for the graduation procession. The Van Wickle Gates, Brown University (4) On the first day of classes in September 1965, I walked alone through the grand inward swinging gates, and vowed that I would exit four years hence with the Class of ’69. However, having taken leave of the campus in February 1968, that was a box that remained unchecked all these decades. It was with full appreciation of the traditions associated with the gates, as well as my arduous wrestling with the demons of the past, that I chose this year to take my place with the Brown University Class of 1969 and pass through the Van Wickle Gates to commemorate the 50th reunion of our class and my first return to campus, now as a proud alum.(5) ---///--- I did it! It was stupendous! Memorial Day weekend was devoted to class reunions and Commencement exercises at Brown. Friday and Saturday provided much joy as I reunited with guys (and a very few gals) who were part of my life at Brown. I’m a bit of a reunion junkie of late. With my high school 50th and architecture school 40th reunions in recent years, I’ve come to deeply appreciate the perspective on life that such gatherings afford. This was no exception. There was ample time to socialize with old buddies, as well as with folks whose names and faces I never really knew well and, in many cases, not at all. There were thought-provoking programs allowing us to examine such topics as the revolutionary curriculum reform instituted just after I left (such the pity), the Black Student Walkout of 1968 demanding true inclusion of minorities, as well as the impact of the Vietnam War on class members whether we were gung-ho ROTC trainees, strident war protesters, or anywhere in between. One highlight was a visit I made to the current Brown University Marching Band as they rehearsed for Sunday’s commencement festivities. It is their tradition to listen to firsthand accounts of the band’s history from returning band alumni. I gladly joined my two closest friends from our days in the band to share some memories. Not only did I give them the backstory of the creation of Elrod Snidley, but I also, spontaneously, took the opportunity to pass on some hard-earned advice, suggesting that they not take things overly seriously when they are faced with challenges—I consider myself living proof that things change! ---///--- All along, it was really about Sunday morning and the commencement processional. The way it is customarily choreographed is for the band to lead the graduating class through the gates, followed by the faculty and the alumni, by year, beginning with the oldest. Each group proceeds down the street with individuals peeling off to one side or the other as they go, creating an ever-lengthening corridor of admirers cheering the succeeding marchers. That’s great fun in itself. It becomes a long, long line of revelers on each side of the street that stretches out of sight down College Hill. As the few classes ahead of ours made their way through the gates, my sense of anticipation grew. Finally, I arrived at the mythic threshold to the campus. My two band buddies, seasoned veterans of this annual event, had intentionally moved ahead of me, all the better to capture “my moment” on their iPhones. I am so glad they did, given that their photos and videos convey what I can barely put into words. The scene was pretty much a ragtag bunch of gray-hairs waving tiny Brown pennants. Many classmates were clad in brown commemorative t-shirts designed for our class by famed New Yorker cartoonist and Brown art professor emeritus, Ed Koren. The steady cadence of a bass drum punctuated the whoops of the crowd. Suddenly I appear amidst the crowd, walking noticeably slower than those around me. Clearly I want to savor this moment. With pennant raised high in my right hand, I pause for a photo op and raise my left hand just as high—two outstretched arms capturing the expansive energy of the moment. Fellow classmates, oblivious to the ritual I am living, continue streaming past me as I am holding the moment in time and space as long as I can, finally taking two steps that complete my passage beneath the iron arch. As I stride, I bend my neck backward, looking up, bringing my hands to my mouth, blowing a kiss to the gates or to the heavens, uttering an audible sigh of contentment. My slow steps turning into a saunter as the grin on my face widens even further. The last group in the procession—the most recent alumni—passed through the gates. Then, in order, the previous marchers left their positions along the side of the street cascading through the throng below them like a sock folding inside out, allowing every participant to pass by every other participant. Our class, being among the eldest alumni, was one of the earliest groups to march down, so in this second phase we passed by many more on the sidelines than we had at first. It seemed that spirits were continuously rising. Given that our class was well established in Brown history as being responsible for the radical curriculum change that has made Brown one of the most desirable institutions of learning, and perhaps with some prurient chortling at the Class of Soixante-neuf thrown in, there were great cheers for us as we walked down the hill. The pace seemed to quicken as I strode along slapping countless high-fives, spontaneously bestowing blessings of peace, love, happiness, prosperity, satisfaction, upon every eager hand and face among those in cap and gown. It was the closest experience I’ve had to emulating the loving bestowal of blessing I saw my brother so freely give in his final days. It answered the question I have often asked since, “Is it possible to spread love and blessing without having a fatal diagnosis?“ Indeed it is. Granted, this was a unique set of circumstances. Nonetheless, it was pure joy. ---///--- At last, I had taken my triumphal march through the Van Wickle Gates! The vow I had made as an entering freshman so many years ago, only needed a little modification to become realized. What I eventually accomplished—without respect to the timing—was to march through these storied gates with my classmates as an educated man. What more could I ask for? Ironically, I was not the only member of the Class of ’69 who received this delayed gratification that morning. As it so happened, none of my classmates walked through the gates in 1969. The political unrest was such back then, that the administration was afraid that our activist class would stage a disruptive and embarrassing protest. Thus, they used the flimsy excuse of mildly inclement weather to move graduation indoors to the hockey arena that year. The Van Wickle Gates have acquired numerous legends and superstitions over the years. The Brown Alumni website acknowledges the history and mystery of the gates on a page devoted to them. They close their posting, as shall I, with this piece of insight based on the etymology of the word gate:

I couldn’t agree more.

Deepak Chopra advises to act with focused intention and detachment from results. Sometimes that opens a space for results greater than imagined, such as today. Our daughter, Becca, was advised by her doctors at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital to schedule the delivery of her son a full month in advance of the due date. Hers was a high-risk pregnancy. It would require the presence of two surgical teams—one to deliver the baby by Caesarean birth, and the second to perform critical surgery on Becca to assure her welfare. Aside from the serious medical challenges, we also realized that a traditional Brit Milah might be impossible. We could not predict how long the baby would be kept in intensive care, when he would be discharged from the hospital, or when he would be healthy enough for circumcision. A lot of alternative scenarios were contemplated, but no decisions could be made in advance of the facts. Some facts emerged yesterday, as we learned that the baby was to be discharged today, and his circumcision was scheduled for 10:30 a.m.—coincidentally on his eighth day of life. We did not know if the designated doctor would allow any family members to be present, nor if the moment would allow for any ritual observances. Nonetheless, I set my intention on the best possible outcome by preparing a brief Brit Milah service with the customary prayers printed on a handout for any and all attendees. At most, that would likely be restricted to the baby’s parents, two sets of grandparents and, of course, the surgeon. Fate seemed, at first, to be unkind. Heading up to San Francisco from Palo Alto, Route 101 was jammed. GPS suggested an alternate route that would barely get us to the hospital in time even if parking and getting through security were seamless and timeless—which they never are. Moreover, Becca texted that, in a rarity, rather than being behind schedule, the medical staff was actually moving the procedure up fifteen minutes. In addition, only the parents would be allowed to be present during the procedure. No way would we be there in time, even if it were only to hang out nearby. Rather than tensing up, cursing the traffic, the hospital, and God, and not even mindful of Deepak’s words at the time, I somehow naturally adopted his philosophy and allowed myself the liberating feeling of letting go. “It’ll be fine,” I told Debbie. After more than an hour and a quarter on the road, we reached the hospital at 10:30. I dropped Debbie off at the entry and headed for the parking structure. Miraculously, a space opened up before me on the second level, unlike the previous visit where I had taken the long serpentine climb to the tenth and uppermost level before finding a spot. When I arrived in the baby’s intensive care room he and his parents had not yet returned from the procedure. Our machatonim, Steve and Cheryl, were there along with Debbie, and a chaplain who just happened to be paying a visit at that time. I told her what our hopes for the morning had been, and that I had even prepared some prayers for the ritual. She readily understood and quickly added that she was Jewish. I suggested that perhaps we could all perform the service after the fact, but that I had forgotten to bring some wine for the Kiddush. She volunteered to search for some, presumably in the spiritual care office. Soon after the chaplain departed, Becca, Josh, and the baby arrived. To our surprise and delight they described how the pediatrician assigned to the procedure happened to be Jewish. While many babies are arbitrarily circumcised just before leaving the hospital, Becca mentioned to the doctor that today was actually the baby’s eighth day, and that they were hoping to say a few prayers. The doctor was delighted! She had a little boy of her own and could relate. Moreover, despite having performed thousands of circumcisions, she had never done one on the eighth day as commanded, let alone with the traditional blessings. She asked Becca to email her the service that I had sent to Becca the night before, in order that the doctor print copies of it for their use.

The service begins with the milah prayer that is customarily said by the mohel. Under the current circumstances I had little hope that the doctor involved would be up to doing that, so my notation in the handout was for that prayer to be offered by the “Surgeon or Parent.” This surgeon, however, did not hesitate to speak the words, Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu al ha-milah. Becca and Josh were sitting just outside the surgical room. Their vision of the baby was obstructed by the doctor, but they were within earshot. They responded with the translation, Blessed are You, Adonai, guiding spirit of the universe, who has sanctified us through Your mitzvot and ordained circumcision. After performing some technical preparations, the doctor informed Josh and Becca that the circumcision was beginning. That was their cue to say, Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l'hakhniso bivrito shel avraham avinu v'sarah imeinu. Blessed are You, Adonai, guiding spirit of the universe, who has made us holy with Your commandments and commanded us to bring our son into the covenant of Abraham our father and Sarah our mother. There it was—all (or certainly most) that I had truly hoped for—the ritual of circumcision with the requisite blessings! We waited some time for the chaplain to return with the wine, but the exigencies of the baby’s needs as well as some follow up appointments of Becca’s, forced us to move ahead with the remainder of the service without the Kiddush. (I suspect that the Kiddush here is designed to make wine available for the baby’s comfort as much as anything else! Our baby was peacefully asleep at this point so we were quite willing to continue without the wine.) We moved on to officially give the boy a name. With parents and grandparents all in attendance, I read, Eloheynu v'elohey avoteynu v'imoteynu, kayem et ha-yeled ha-zeh l'aviv u-l'imo, v'yikarey shmo b'yisrael Shmuel Etan ben Yehoshua v’Rivkah. Baruch atah Adonay, koreit ha-brit. Our God and God of our fathers and mothers, sustain this child for his father and mother. May his name in Israel be called Shmuel Etan son of Yehoshua and Rivkah, and Samuel Eugene Shapiro in English. Blessed are you, God, who establishes the covenant. I couldn’t say if there was a dry eye in the room as I was too filled with joyful emotion to observe. We all recited the Shehekheyanu, expressing gratitude to be alive in that moment. Josh and Becca lay hands on their son and recited the priestly benedictions. And lastly, and again with much emotion, Becca recited the Gomel prayer—words of gratitude for surviving childbirth, serious surgery, or, as in this case, both. If we had had perfect foreknowledge of all the factors influencing this morning—the timing of the procedure, the traffic, the doctor’s religion, the hospital rules, etc. we could not have planned a more deeply experienced, heartfelt, and joyous sequence of events. I knew when I arranged the service folder and sent it to Becca that it would seem like too much to orchestrate given all the other physical and emotional challenges of the day. In an attempt to relieve her of the feeling that I was pressuring them to do more than was desirable or even possible, I had texted her last night, in complete honesty, “Prepared for the full range of possibilities. No worries.” That range was from absolutely no ritual observance, to the possibility of doing what was written on the handout—if not in the hospital then perhaps later at home. Deepak was right. The intention was set. The outcome was left open to circumstance. Our patience and fluidity led to the consecration of this precious boy that exceeded all expectations. Baruch hashem. My email message read: Two boxes of Rabbi Sidney Ballon's sermons are en route to you via UPS. Delivery is expected Friday. Attached is the signed Deed of Gift. And with that, after nearly forty-four years in my possession, my dad’s papers are on their way to their final resting place, the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati, Ohio. The end of an era for me. I “inherited” these documents much too soon, at the age of twenty-seven, upon my father’s death. Now, at the ripening age of seventy, I bequeath them to the generations of students and scholars, who, I am assured, regularly peruse these archives. After my intense scrutiny of these eight hundred or so sermons plus many other speeches and articles—over two million words—it most definitely tugs at my heart to send them off.

I inquired of my chevra as to the proper ritual to mark this departing. I got intelligent and meaningful suggestions. In the end I simply lifted two well-packed cardboard boxes onto the counter at the UPS store. (After summer jobs in our youth Dad and I shared a bit of pride in our packaging skills.) I inserted my credit card in the reader, affixed my electronic signature, took the receipt, drove home, put away the hand truck that assisted my transport of the cartons, walked into my room, pressed our shofar to my lips, and gave Dad a tekiah gedolah on this second day of Elul 5778. More will follow. Our family will gather in early December, a year after the launch of the book, A Precious Heritage, in which I bequeathed to them thirty-six of my favorite of Dad’s sermons. What exactly we will do at this year’s gathering I cannot say for sure, but it may involve a combination of some of the suggestions offered by friends and family. Havdalah, a piece of art inspired by Dad and his sermons, kaddish d'rabbanan, and a big deli spread, rise among the possibilities. One more thing. The legacy of my father’s essays—preserved not only in the book, but also in dozens more transcribed and/or scanned to my webpage—still seems somewhat thin compared to the fullness of holding the actual aging pages in one’s hands. To make up for for that, I have withheld from the American Jewish Archives the selected thirty-six sermons, and replaced them with photocopies. The originals remain with me for now, soon to be placed in a 9x12 black clamshell metal-edged archival storage box. Who knows, maybe the uneven impressions of Dad’s fading typewriter ribbon, his pencil scrawl edits, and his now rusty paperclips will one day be held in the hands of another generation of readers. Maybe not, but I will at least allow for the possibility that my future septuagenarian grandchildren might experience these pages with some awe and wonder about their ancestor, Rabbi Sidney Ballon. Oh, I guess there’s one more piece of the ritual…I wrote this. |

AuthorFor access to 77 postings on my previous Yesh Indeed blogspot.com site CLICK HERE. Archives

December 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed