|

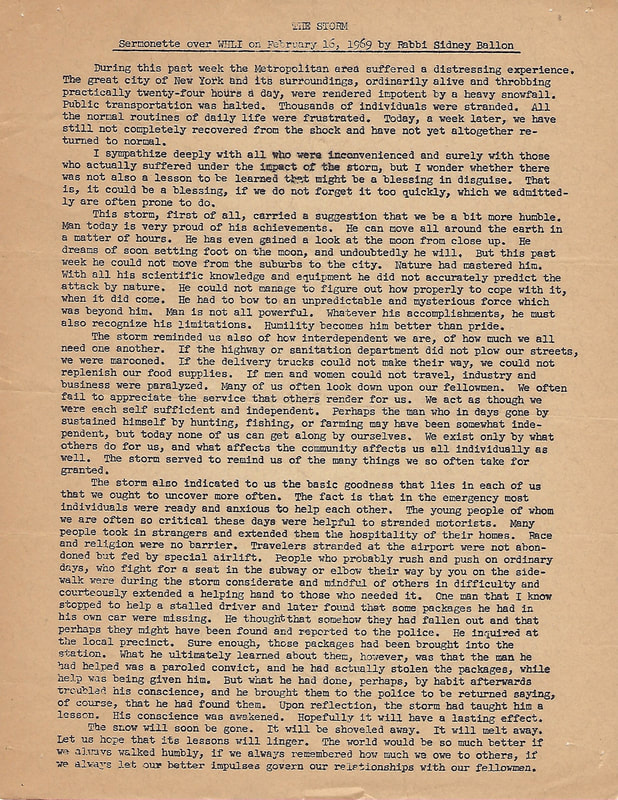

My father's radio sermonette from 1969 speaks to today's coronavirus crisis. [We] had to bow to an unpredictable and mysterious force which was beyond [us].

0 Comments

Yesterday there was a stranger in the side yard of our home, not particularly well-dressed, asking to come into the house. I didn’t know who he was. I didn’t know why he was in our yard. I didn’t think he belonged there. I was reluctant to let him in. When I refused him entry, he made menacing gestures and remarks. Then, fortunately, I woke up.

This morning my dream was less threatening and was easily understood. There was no metaphor about the threats we may feel to our secure environments. It was a literal conversation, if not harangue, about the dangers of the pandemic. I was being admonished for touching my face. I woke up with an urgent feeling that I needed to wash my hands. It doesn’t take a Joseph to realize that coronavirus has invaded my dreams. For this I’m actually grateful. I don’t believe there are any bad dreams. Each dream carries an important message. When my subconscious causes me to pay attention to things I’ve been overlooking, it’s up to my conscious mind to do just that—to inquire of the dream, what is it that I am missing here? Sometimes I do that quite literally. This morning I didn’t go through a formal dream interpretation process, but I did notice the thoughts that arose in the few moments after I awoke. Like many of us, I noticed that in recent days there are people who are reaching out, demonstrating kindness and concern, and that I too have had a greater urge to reach out to others. Names from the past keep floating through my mind. Why would I think about a boss that I had nineteen years ago—other than to realize how important his wisdom and his kindness was toward the success of my career. Why would I think about a classmate from nearly fifty years ago—except to realize the importance of a friendship that has endured over the decades. In the current climate I feel the urge to do more than think about the people who have made a difference in my life. I have begun contacting them. A question that continually goes through my mind takes me back to the two and a half years during which my brother was living with the severe diagnosis and prognosis regarding his glioblastoma—his terminal brain cancer. It was a time in which I watched him go on a pilgrimage of love. His heart was wide open. He went everywhere he could, searching for old friends and family to give love and blessings. In his fragile condition, he traveled from his home in Alabama to South America, twice to Europe, multiple trips to New York and California, and I’m sure lots of places I’m not even aware of. Everywhere he went he was bestowing love and blessings. I’ve always wondered why it takes a fatal diagnosis for someone to be able to open his heart in such away without being considered crazy. I still don’t have the answer, but I am aware of the opportunity that this pandemic offers. Suddenly all of us are facing an existential threat. Never before have so many people been aware of the reality that has tacitly accompanied them every day of their lives—that they and their loved ones are mortal. With that awareness comes greater permission to be loving without being thought insane. Before coronavirus, consciousness of one’s own mortality was not all that accessible to most of us. Intellectually, we all knew that we would die, but it was much harder to deeply take in that awareness and get a full sense of the finitude of our lives, not to mention the harsh reality that even the next day is not guaranteed. Every day we would walk through life with a sense that I’ve got this. Things are under control. I can make plans with clear expectations that they will come to fruition. That’s no longer the case. The sense that things are under control was always an illusion. Nothing is that certain. Now many of us are experiencing the discomfort of uncertainty and the fear that accompanies it. Uncertainty is actually pretty powerful. It strips away the illusion that things are under control. With that comes gratitude for each day we are given and for the opportunity to continue to learn, to create, to be in relationship, and to make a difference in the lives of other people. The Psalmist said, Teach us to number our days that we may nurture a heart of wisdom. He didn’t say a brain of wisdom. We already know everything we need to know about our mortality. With a heart of wisdom we may understand how precious each day is and how precious each life is. If we use these days of global crisis to nurture a heart of wisdom, we will grow in our capacity to be open, to reach out, and to bestow blessings and love. In 2008 I was among over a hundred cyclists who rode from Jerusalem to Ashqelon down through the Negev to Eilat, approximately three hundred miles. Upon my return I spoke to the congregation about the impact the ride had on me. The words I spoke then, that continue to linger in my mind, are as follows-- There were quiet moments too, when the group had spread out, when I had the entire road to myself as far as I could see. As alone as I was, with little to be heard other than the sound of my own bicycle rolling across the pavement, I would still feel secure in knowing that I was part of an amazing supportive, loving community. To be that alone and feel that connected was very sweet. What brings this to mind today, is yesterday’s experience of worshipping virtually with the streaming Power Hour minyan. In some ways this was the most “powerful” Power Hour of all. I felt emotional twinges throughout, as I imagined my fellow congregants, absent from the empty pews that the video camera unintentionally and ironically focused upon. I was filled with appreciation at the challenge Michael, Bill, and Rabbi Ezray not only accepted, but generously and bravely met in deeply connecting with us despite the discomfort of speaking to an empty room.

I sit next to Debbie almost every week in the Beit T’fillah. This week we were together, but sequestered to my home office, viewing the service on my computer screen. I donned my kippah and tallit this Shabbat, as I would normally do in shul, but not normally do at my desk. It was an important part of creating the ritual space, as we brought our full imagination to conjure up the people and the place from which we were separated. In addition to feeling connected to the virtual community, there was another unanticipated benefit as I more keenly appreciated the blessing of having Debbie at my side. The service was reminiscent of the virtual funeral I facilitated by conference call when my mom was buried shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. That day, since travel was so uncertain, twenty friends and family dialed in from around the world. From their reports, some callers’ experience of the funeral was more vivid and emotionally charged than for those at graveside. I likened it to listening to old-time radio where listeners had to bring their imaginations to the broadcast, rather than passively receive images as on television. None of us knows how long we will have to sustain this virus-imposed segregation. The more we experience “social distancing” the more we realize how dependent we are on social connection. Thank God, and thank Congregation Beth Jacob that we can still feel secure in knowing that we are part of an amazing supportive, loving community. To be this alone and feel this connected is very sweet. V’shamru v’nai-Yisrael et-hashabbat… The Children of Israel shall keep the Sabbath… Exodus 31:16 Keeping the Sabbath—what does it mean? As a kid, growing up in the home of a Reform rabbi in Metropolitan New York, in the Fifties and Sixties, I had a pretty clear understanding of what it meant to observe Shabbat. (I didn’t equate that with keeping it or guarding it as the term Shomer Shabbes translates.) There were just certain things we were expected to do or not do in order to observe Shabbat.

In our home, throughout the week we ate dinner as a family at six o’clock sharp—every day. Family dinner on Shabbat was a cut above. Tablecloth. Good china. Candles. Kiddush poured from my grandmother’s cut glass decanter. Challah. A special meal. When we got to a certain age we regularly joined the folks at services, as well. Saturday was more about what we did not do. We didn’t work. It was probably the one day of the week that one or more loads of laundry did not tumble in the machines in the basement. We did not engage in commerce. There were no shopping trips per se. There were some exceptions. The West Hempstead Rams played their football games on Saturday afternoons, and basketball on Friday nights. There were the occasional Friday night dances. If we had to dip into our pockets to pull out a quarter for entry to a high school event, that wasn’t exactly shopping. I suppose that Dad was less than thrilled that we were going to these events, but he must have decided to be selective about picking his battles. Our family was not Shomer Shabbes. We were Reform Jews. We drove to temple. We turned lights on and off. We tore toilet paper. Relative to some of my peers, however, we were pretty far to the right. We toed the mark my father set, one that hardly existed in other households. A generation later, as I pretty much set the standard for Jewish observance in the home we created in Palo Alto, family life was somewhat different. Our children had many extracurricular activities. Five of us gathering at the same table, at the same time, night after night, was a rarity. The one constant, however, was Shabbat dinner. On Shabbat, the kids were expected to be home for dinner—tablecloth, candles, good china, kiddush poured from my grandmother’s cut glass decanter, challah, and a special meal. About twenty years later, as I was attending Davvening Leadership Training Institute. I was talking with my instructor, Rabbi Marcia Praeger. I don’t recall the exact content of the conversation, until the moment when I said to Marcia, somewhat apologetically “I’m not Shomer Shabbes,” to which she replied, in so many words, “We all get to decide how we choose to guard Shabbat. We don’t have to let others define that for us.” What a validating and liberating declaration! That’s how I became Shomer Shabbes—not from becoming more stringent in my practice, but in honoring the practices I maintain to keep Shabbat alive in my life, for me and my family, and for Israel. My father spoke from the bimah more than once about how liberal Jews of the day should not define their Judaism by what they don’t do --I don’t wear a kippah, I don’t keep kosher, etc. They must bring their minds and their souls to the task of understanding what, among the mitzvot, rings true for them, what they choose to practice in order to add meaning to their lives. When I reflect on those formative years in my parents’ home, I recall how, as a member of the high school marching band, I had a regular Saturday afternoon gig throughout the fall, supporting the football team and entertaining the crowd with music. On one of those days, quite unexpectedly, and to my great delight, Dad miraculously appeared at a game. He must have, on that autumn day, weighed the value of family versus that of Shabbat halachah, and family rang true for him. The Union Prayer Book with which I grew up, contains a notable line from the Zionist thinker, Ahad Ha’am, “Even as Israel has kept the Sabbath, so the Sabbath has kept Israel.” In an era where new paradigms of Jewish practice are evolving, exactly how that’s done is up to each one of us. |

AuthorFor access to 77 postings on my previous Yesh Indeed blogspot.com site CLICK HERE. Archives

December 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed